#048 Why India Is the Strategic Opportunity the World Can’t Overlook

Fri, 12 Dec 2025 06:45:53 GMT

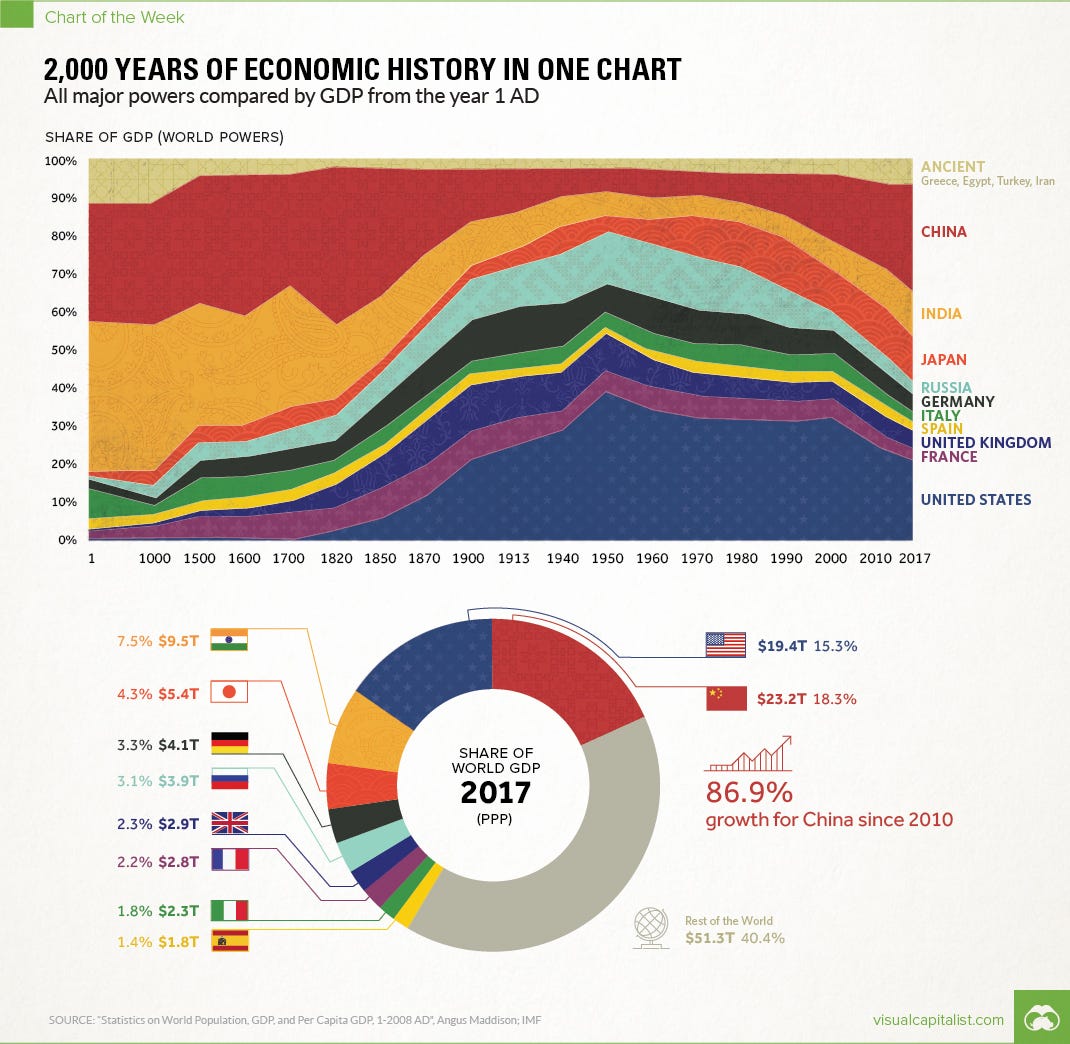

Cornerstone Ventures

Two thousand years ago, India commanded a substantial share of global GDP. That dominance eroded over nearly 300 years of colonial rule, leaving the country with a minimal economic base at independence in 1947. Since then, India has had to rebuild from the ground up—but it is now clearly re-emerging.

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/2000-years-economic-history-one-chart/

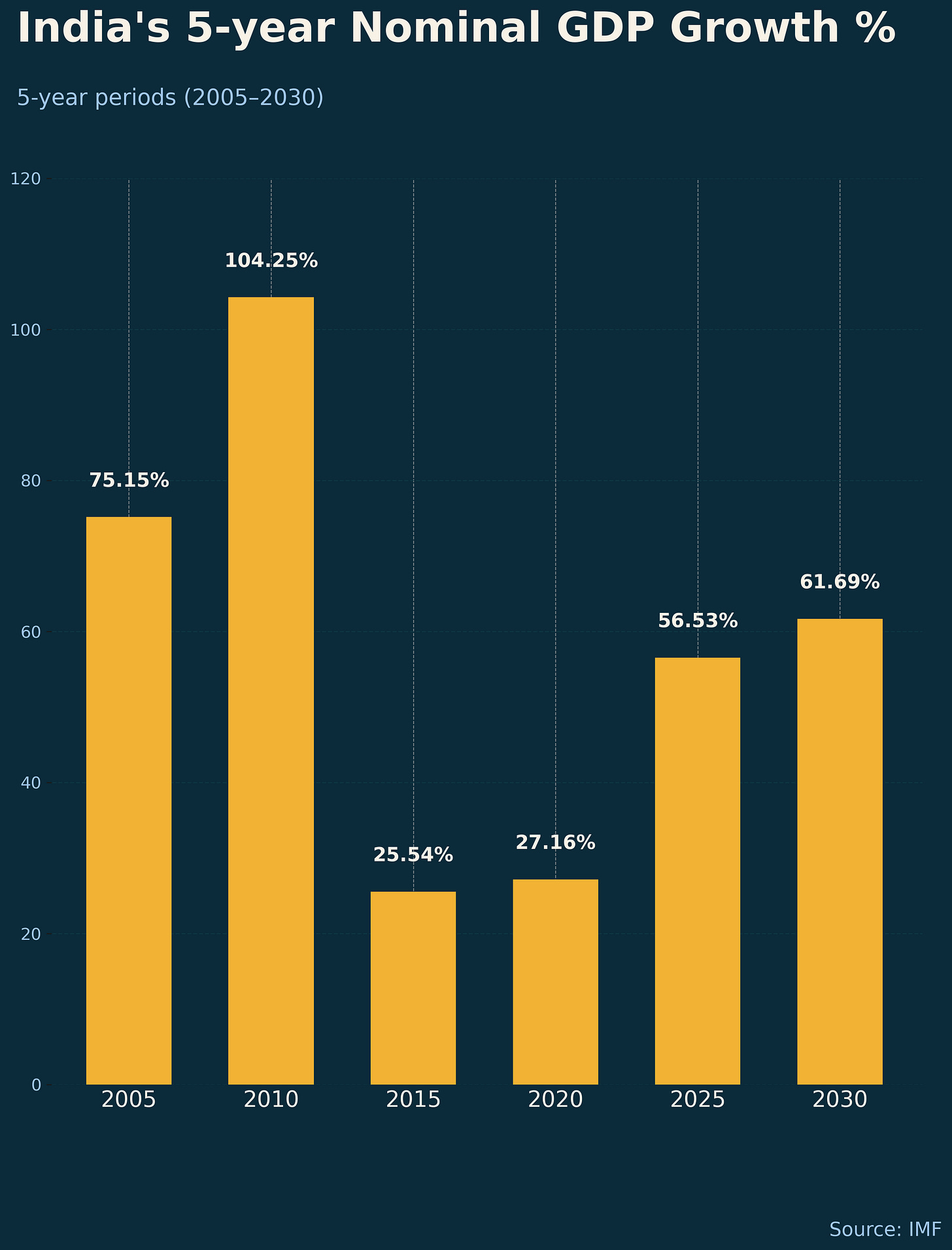

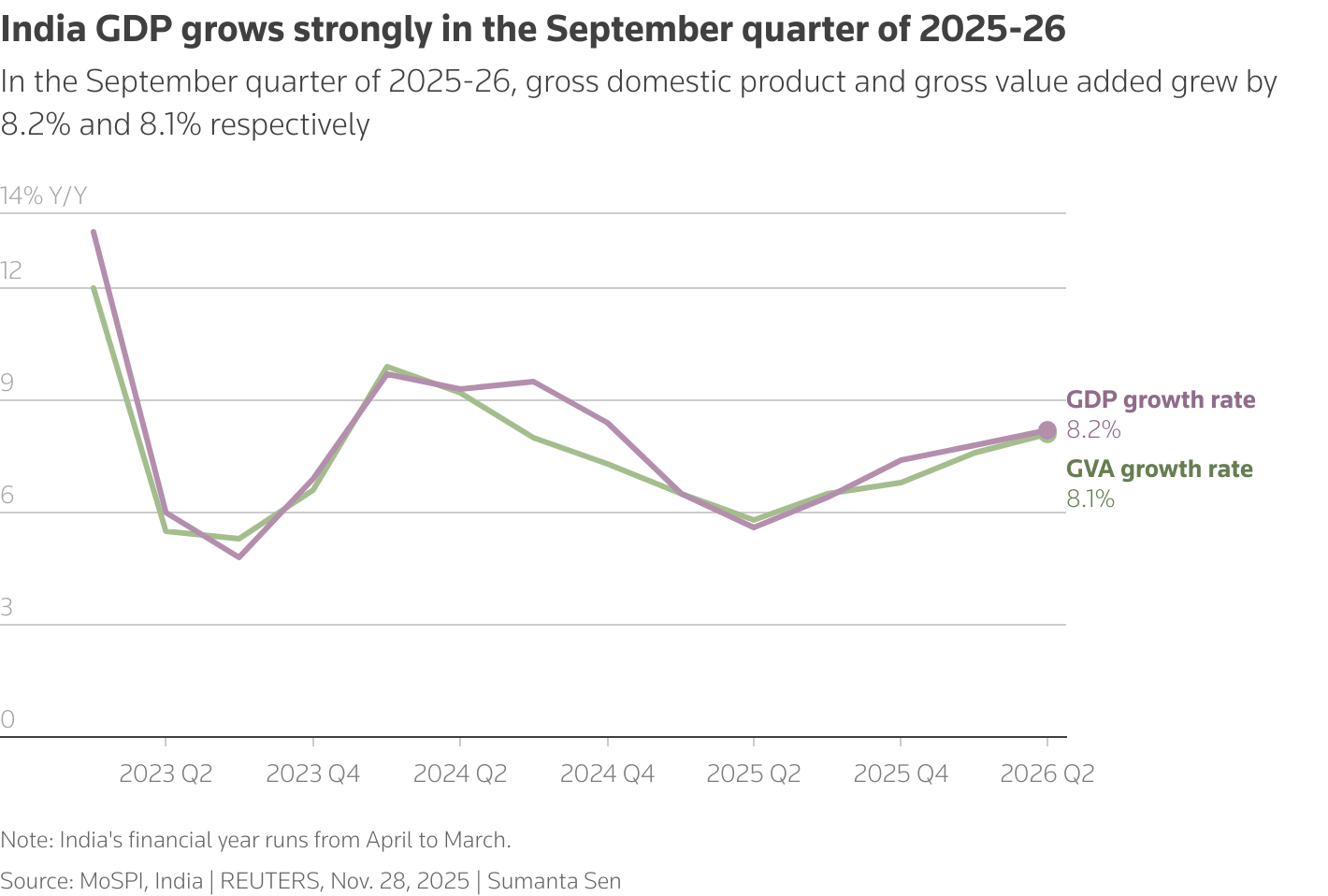

Today, India’s GDP stands at $4.12T, making it the world’s 5th-largest economy and the fastest-growing major economy for the past two years. With forecasts projecting sustained growth above 6% for the next decade, India continues to demonstrate resilience—even amid global protectionism, tariff pressures, and periodic geopolitical conflict, including a brief war with Pakistan.

There are a number of structural factors that support this assertion. Some that we consider significant are listed below:

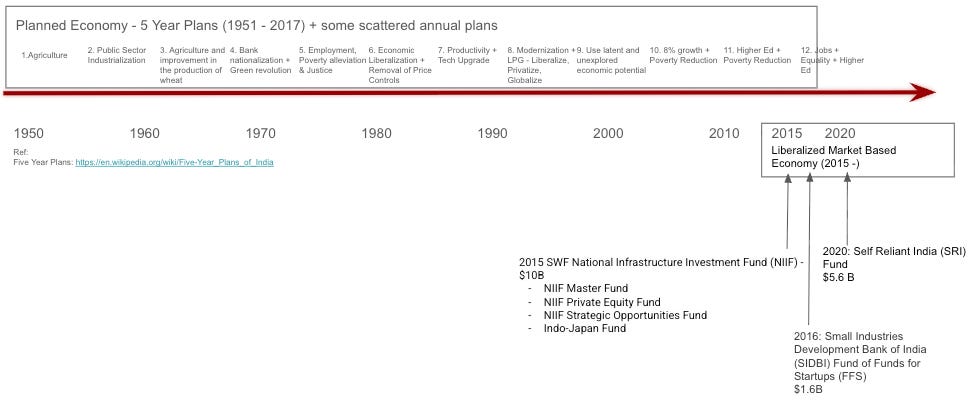

Transition from a Planned economy to a Liberalized market economy

Starting from an extremely small economic base after independence, India adopted a planned-development approach to build foundational industries. Concerns that domestic companies might be overwhelmed by foreign competition led policymakers to implement protectionist measures and market-entry controls, giving local industries the space to mature. Progress was gradual and not without missteps, but by the 1990s India had built a strong sectoral foundation—positioning the economy for rapid expansion once liberalization began.

India’s National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIIF) is a sovereign linked infrastructure fund anchored by the Government of India and established in 2015 to attract investments for India’s infrastructure sector. It operates as a collaborative investment platform with government and private capital, with a focus on sectors like transportation, energy, digital infrastructure, and other high-growth areas. As of early 2025, it had $4.9 billion in total assets under management targeted to $10 billion. Initially, the Government of India held 100% ownership, but its stake has been reduced to 49%, with the remainder held by foreign and domestic investors like the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) and Canada’s PSP Investments. The overall goal of the fund is to catalyze private and public investment in commercially viable infrastructure assets of national interest.

SIDBI’s Fund of Funds (FoFs) are a collection of funds designed to provide indirect capital to startups and MSMEs in India, originating from initiatives like the Startup India Action Plan launched in Jan 2016. The main FoF is the Fund of Funds for Startups (FFS), with a 10,000 crore ($1.1B) corpus managed by SIDBI, aimed at investing in Alternative Investment Funds (AIFs) which, in turn, invest in startups. Other FoFs include the ASPIRE Fund for rural enterprises, UP Startup Fund and the Odisha Startup Growth Fund.

The Self-Reliant India (SRI) Fund was launched in 2020 as part of the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan (Self-Reliant India Mission) to support Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). The fund’s total size is 50,000 crore INR ($5.6B), with 20% funding from the government and 80% from private equity and venture capital funds. Its focus is to provide equity and quasi-equity growth capital to viable, high-potential MSMEs, helping them scale up, innovate, and become national or international champions. The fund is an FOF being implemented by NSIC Venture Capital fund Limited (NVCFL).

Political & Economic Setup

Political:

India’s political system is a federal parliamentary democracy with powers distributed across three levels of government: Central (Union), State, and District/Local. The Constitution assigns each level specific subjects of responsibility through the Union, State, and Concurrent Lists. Both the Central and State governments operate with executive, legislative, and judicial branches, ensuring checks and balances and preventing any single branch from accumulating unchecked power.

Central Government: National policy, defense, foreign affairs, macroeconomic management, and cross-state matters.

State Governments: Police and public order, health, agriculture, land and local development.

District/Local Governments: Grassroots administration, local infrastructure, essential public services, and direct citizen-facing governance.

Together, these levels form a federal system with strong unitary characteristics—the Centre holds significant authority, yet States and Local bodies play indispensable roles in delivering day-to-day governance and public services.

Administrative Meritocracy:

The Indian Civil Services form the permanent executive branch of the Government of India. They are often described as the steel frame of the administration because they provide continuity, stability, and implementation capacity regardless of which political party is in power. It is a meritocratic organization with very competitive admittance criteria.

The key functions performed by the civil services is as follows:

Implementing government policies & laws

Advising ministers and political leadership on policy options, feasibility and risks, data, economic analysis & administrative constraints

Running day-to-day administration and public service delivery, law and order, revenue collection, national security and intelligence

Managing large public programs & welfare schemes

Regulatory oversight for banking and finance, trade & industry, environment, infrastructure and public utilities

Crisis management and disaster response

Diplomacy and international representation

Maintaining political neutrality and administrative continuity

Economic management & development planning

Upholding the constitution & rule of law

The Indian civil services are a historic and prestigious institution, with roots that predate independent India. Originally established by the British to administer a vast and complex territory, the system has evolved into one of the most respected administrative frameworks in the world. Entry into these services remains highly competitive—in 2023, over 1.3 million candidates competed for just 1,255 positions.

The Union Public Service Commission (UPSC), which conducts these examinations, was first constituted in 1926 under British rule. After independence, the services were restructured and Indianized:

Indian Administrative Service (IAS) — established in 1947, evolving from the Imperial Civil Service (1858) and later the Indian Civil Service

Indian Police Service (IPS) — created in 1948, replacing the Indian Imperial Police (1858)

Indian Forest Service (IFS) — formed in 1966, with origins in the Imperial Forest Service (1867)

Indian Engineering Services (IES) — formally recognized in 1923, with recruitment conducted by the Public Service Commission from 1926 onward

These services collectively form the professional backbone of India’s governance and public administration.

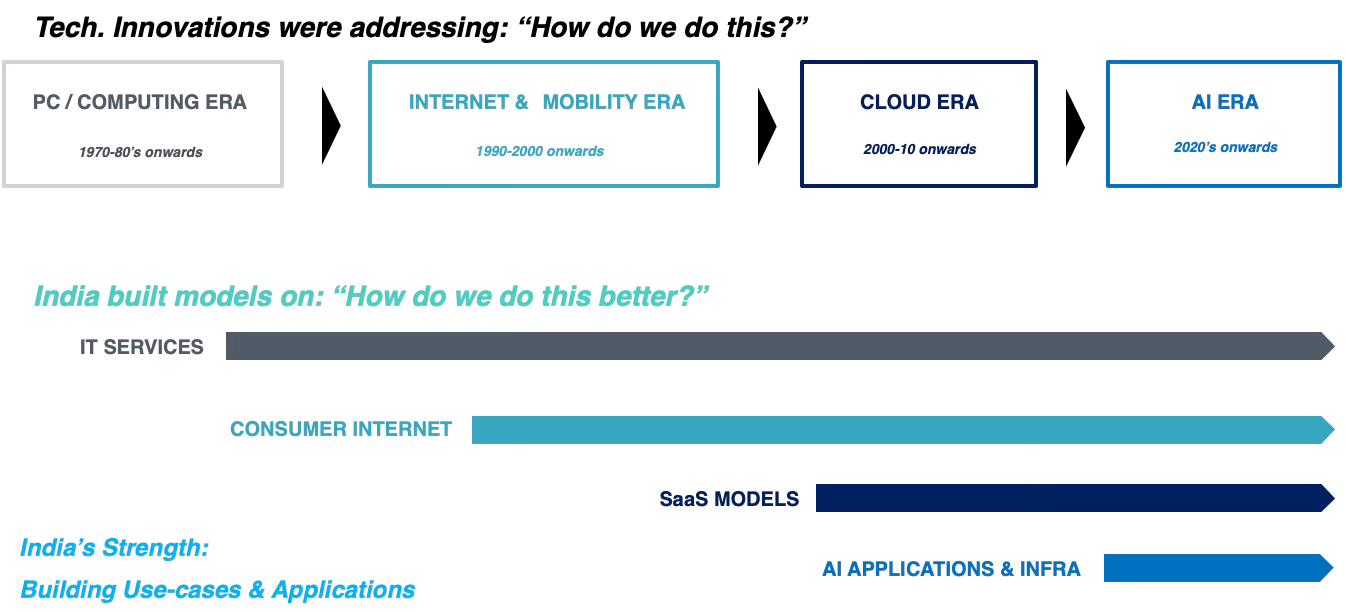

Demonstrated ability to carve out a niche for growth in each tech revolution

Despite multiple tectonic shifts in global technology, India has consistently identified and dominated niches where it could excel. During the rise of the PC and enterprise computing era, India built a world-class IT services industry, delivering quality at globally competitive prices. In the internet and mobility era, it leapfrogged outdated landline infrastructure to create one of the world’s largest consumer internet markets, powered by mass mobile adoption. In the cloud era, India produced globally recognized SaaS companies such as Zoho, Freshworks, BrowserStack, Hasura, Innovaccer, Chargebee etc.

As we enter the AI era, we expect India to play to its strengths once again—building scalable use cases, applications, and increasingly, key layers of the AI application and infrastructure stack.

Public & Private Markets: Policy evolution

Public Markets Policy

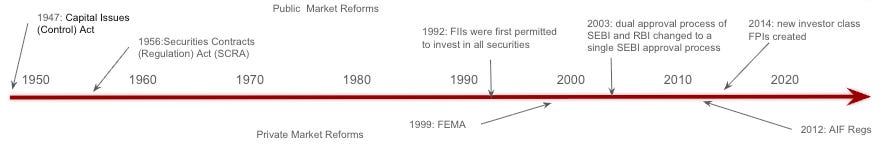

The evolution of public market regulations in India has been a transformative journey, moving from an era of limited oversight to a robust, globally integrated framework. The early years, post-independence, were governed by acts like the Capital Issues (Control) Act, 1947, and the Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act (SCRA), 1956, which focused heavily on government control over capital raising. However, major market scams and the need for economic liberalization in the early 1990s spurred the creation of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), which was given statutory powers in 1992. SEBI’s establishment marked a fundamental shift from a merit-based to a disclosure-based regulatory regime, dramatically enhancing investor protection, market integrity, and transparency. Subsequent reforms, including the introduction of electronic trading (by NSE in 1994) and dematerialization of shares (through the Depositories Act, 1996), stricter corporate governance norms, and regulations against insider trading, have streamlined market operations, reduced fraud, and facilitated the participation of both domestic and foreign investors, culminating in one of the world’s most dynamic capital markets.

The foreign investor participation journey in the Indian markets began with the liberalization of FII regulations in the early 1990s, allowing foreign investment institutions (like pension funds, mutual funds, and insurance companies) to invest in Indian securities within specific limits (e.g., initially capped at 24% of a company’s paid-up capital, which could be raised by a special resolution).

The landmark change occurred in 2014 with the introduction of the SEBI (Foreign Portfolio Investors) Regulations. This regime merged the erstwhile FII route, the Sub-Account (SA) route, and the Qualified Foreign Investor (QFI) route into a single, comprehensive FPI framework, aiming for simplified entry, operational ease, and greater stability in foreign capital flows.

Major Changes Introduced by the FPI Regime

Consolidated Registration and Categorization: Instead of multiple routes, investors register as a single Foreign Portfolio Investor (FPI). FPIs are primarily categorized into two tiers based on their risk profile and regulatory status:

Category I FPIs: Entities with strong regulatory oversight, such as government entities, central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and regulated asset managers. They benefit from simplified Know Your Customer (KYC) norms and operational requirements.

Category II FPIs: Includes all other investors like corporate bodies, family offices, and unregulated funds, subject to stricter compliance.

Ease of Doing Business: The new regulations aimed to streamline the registration process through a common application form (CAF) and provided perpetual registration subject to fee payment and periodic KYC review, replacing the earlier limited-term registration of FIIs.

Equity Investment Limits: The basic individual investment cap for any FPI (along with its ‘investor group’) is less than 10% of the total paid-up equity capital of a listed Indian company. Any investment of 10% or more is classified as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), subjecting it to the FDI policy and sectoral caps.

Debt Market Liberalization: The rules have continuously been relaxed to deepen the Indian debt markets, with measures such as:

Introducing the Voluntary Retention Route (VRR) to provide long-term, stable FPI investments in debt with higher operational flexibility, in exchange for a mandatory lock-in period.

Increasing the overall limit for FPI investment in corporate debt (e.g., from 9% to 15% of the outstanding stock) and relaxing security-wise concentration limits.

Enhanced Transparency: The regulations introduced stricter requirements for the disclosure of Ultimate Beneficial Owners (UBOs) to curb money laundering and promote greater transparency in ownership structures.

These regulatory shifts have been critical in making the Indian public market more attractive, liquid, and aligned with global standards, significantly increasing the reliance on foreign capital for growth.

Private Markets Policy

The policy evolution for private markets in India, primarily consisting of Private Equity (PE) and Venture Capital (VC), transitioned from an unregulated, nascent segment to a highly formalized, classified, and robust ecosystem under the supervision of SEBI. The initial phase in the late 1990s was governed by the SEBI (Venture Capital Funds) Regulations, 1996, which focused narrowly on domestic VCs and their investment limits in unlisted companies, often lacking comprehensive governance standards. The significant regulatory leap occurred in 2012 with the notification of the SEBI (Alternative Investment Funds) Regulations (AIF Regulations), which unified all privately pooled investment vehicles—including PE, VC, real estate, and hedge funds—into a three-category AIF structure (I, II, and III), thereby expanding the regulatory scope, mandating registration, and establishing clear norms for disclosure, investor limits, and investment strategies. Subsequent amendments have continuously tightened governance, increased transparency (especially concerning the Ultimate Beneficial Owners), and introduced mechanisms like the co-investment framework and the Voluntary Retention Route (VRR) for long-term debt investments, successfully positioning the AIF regime as the primary, high-growth vehicle for sophisticated domestic and international private capital.

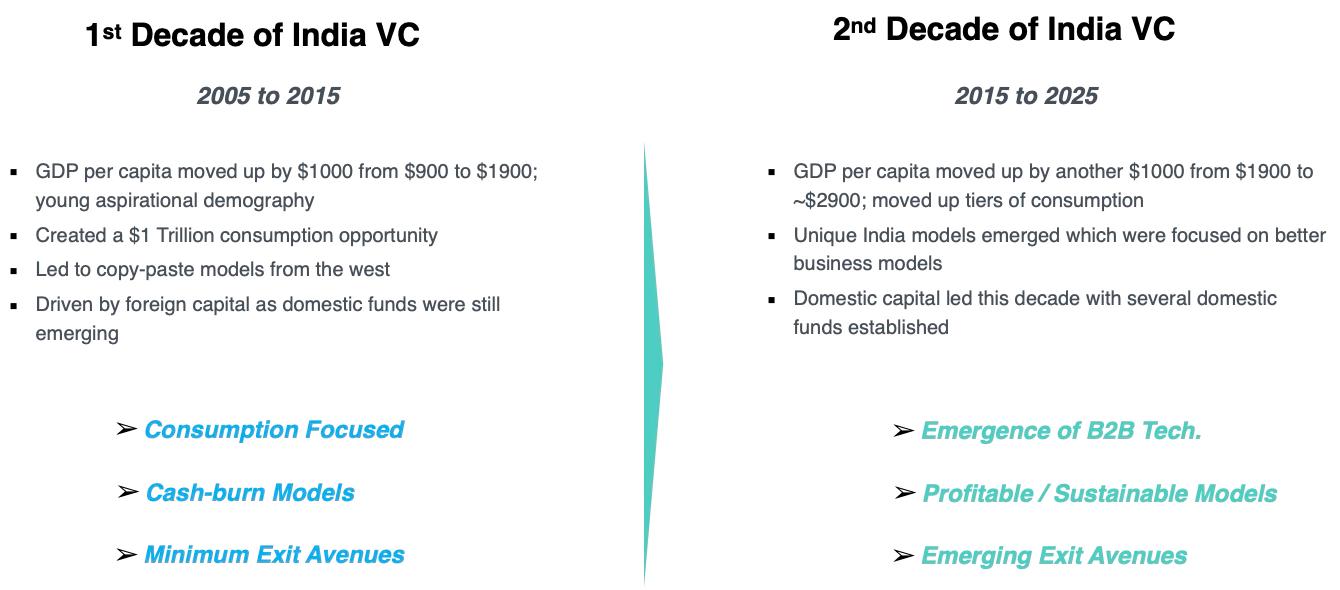

Private markets: 2 decade old VC Model is maturing and showing strength

There were homegrown funds that operated in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but the VC ecosystem really took off in 2005 when a number of global VC funds entered the Indian market attracted by the size of the market and a growing middle class. Per capita GDP went from ~$900 in 2005 to ~$1900 in 2015 and then to ~$2900 in 2025. With over 1B people, that translates to a $1T being added into the GDP every decade. Initially the focus of VC investing was on consumer models, specifically B2C, but the investors soon realized that the Indian consumer was very different from a western consumer and the number of cycles needed to cover customer acquisition cost was much larger than in the western markets, given the value focus of the consumer. Slowly after 2015, the market evolved to also invest in B2B models, where these were companies selling into enterprises, with better pricing power, stable and predictable metrics and visibility into account level profitability.

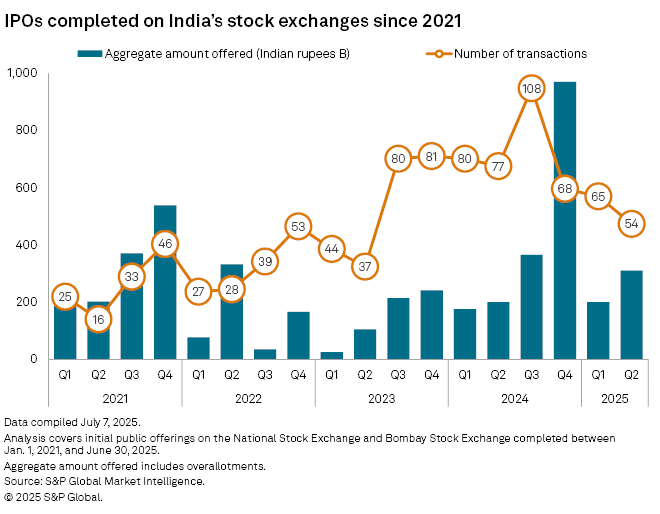

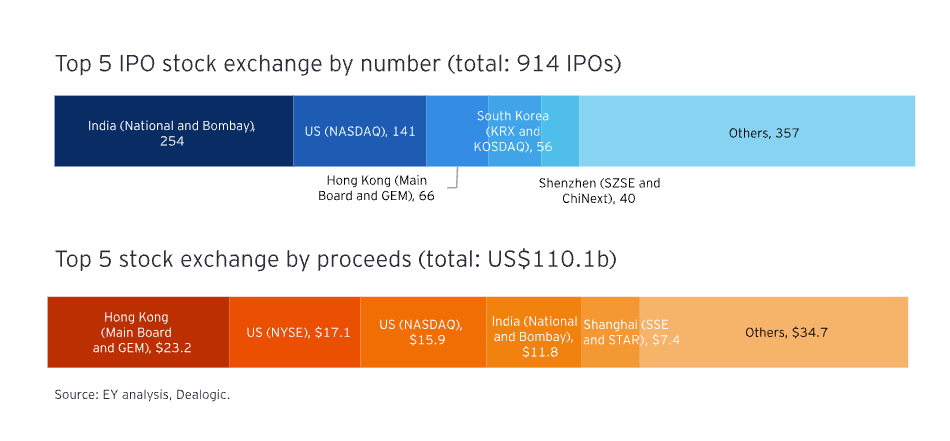

Robust IPO scene

India has quietly built one of the strongest IPO ecosystems globally. A deep pool of domestic investors, high market liquidity, and a steady pipeline of high-quality companies have turned the Indian public markets into a powerful engine for capital formation.

Retail participation is soaring thanks to digital investment platforms, while mutual funds, insurance companies, and pension funds provide a stable institutional backbone. On the supply side, India consistently produces IPO-ready companies across tech, financial services, manufacturing, and consumer sectors—many backed by PE/VC firms that bring governance discipline and transparency.

SEBI’s regulatory framework is widely respected for its clarity and investor protection, further increasing global confidence. As international investors look for alternatives to China, India’s rule-of-law environment and strong economic fundamentals make its IPO market even more attractive.

In short: India’s IPO scene is deep, liquid, well-regulated, and fueled by both domestic conviction and global attention—making it one of the most vibrant public markets worldwide.

2025 Q1-Q3 (9 months data from across the World)

https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/ipo/trends

Domestic public market support for IPOs

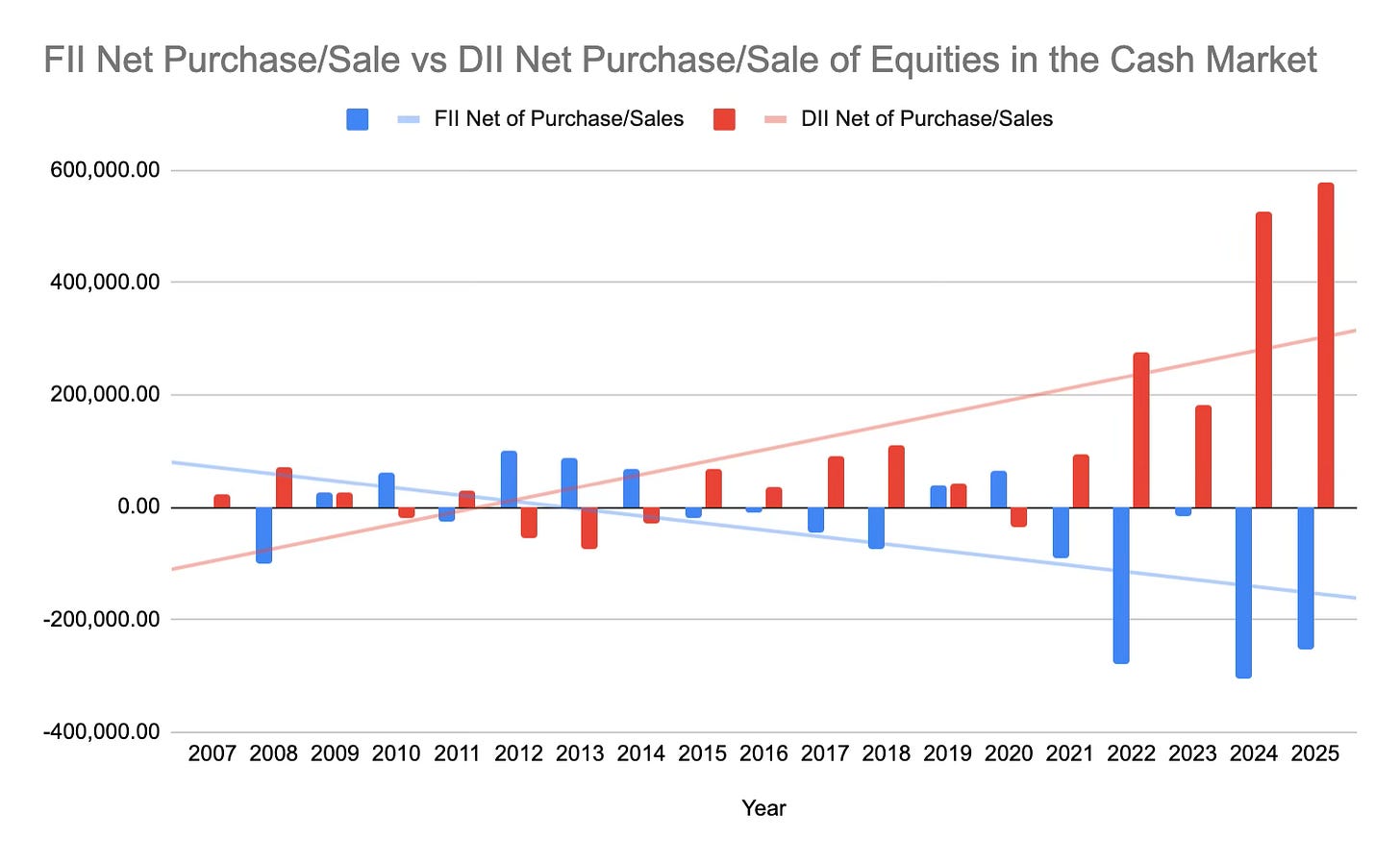

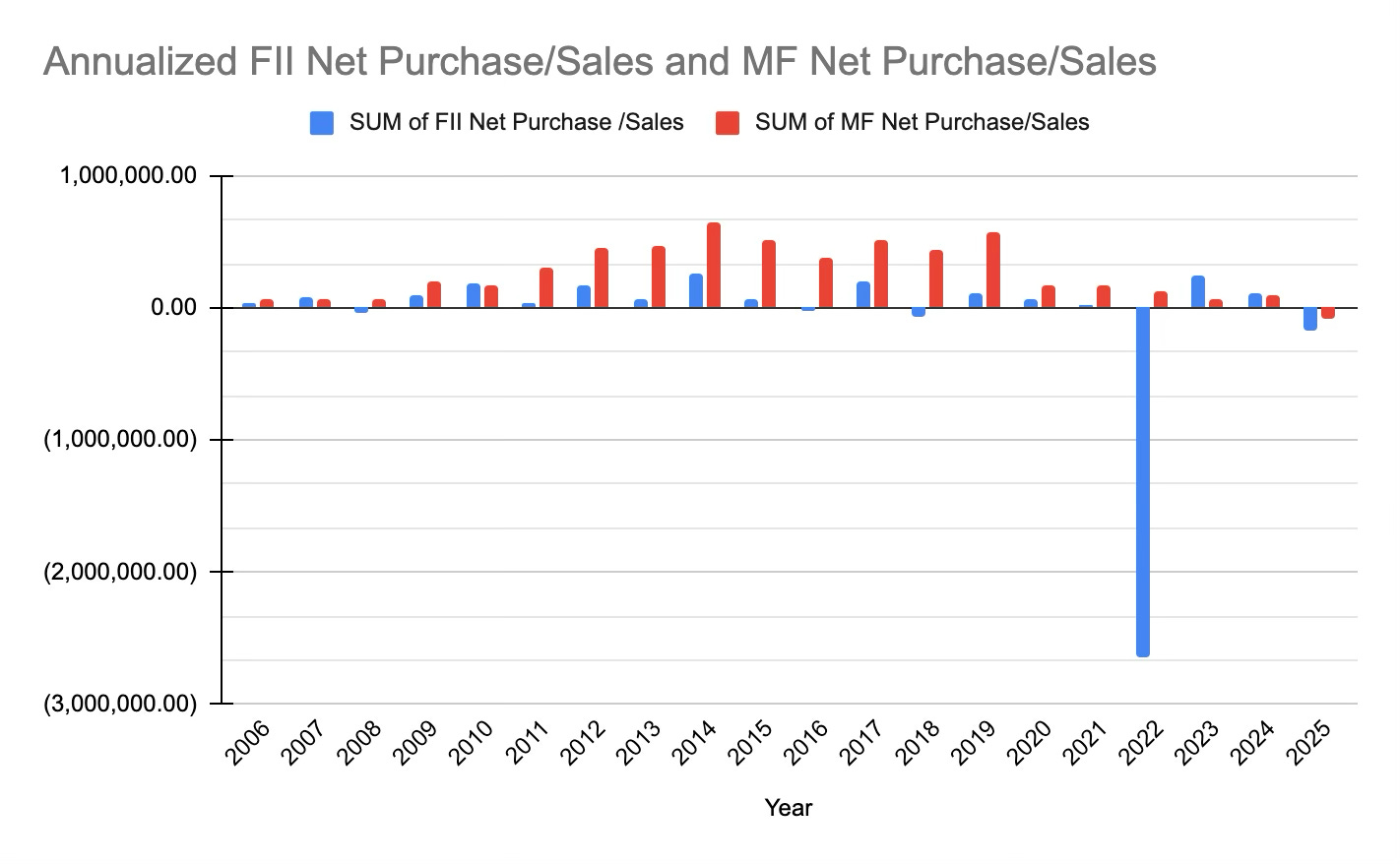

The $2T added to the GDP over the last 2 decades (2005-2025), has shown up in significant portion in the investment appetite for the middle class, that has helped the DII (Domestic Institutional Investors) becoming a significant part of the public markets (rivaling FPI - Foreign Portfolio Investors) and being able to support the appetite for companies going public. The market also has multiple boards - the BSE and the NSE and in addition the SME boards attached to these exchanges with the ability to go public and raise capital. The SME boards have a more relaxed criteria, helping spur the growth in the early and growing SME segment. This support from the DII to the public markets is one reason why the IPO markets are so strong. India currently has the largest number of IPOs in the world over the last couple of years, by count but not by value.

Source: Data from Moneycontrol

Significant Infrastructure Investments & trends

India is rapidly emerging as a global deep-tech powerhouse, anchored by bold national ambitions in space, transportation, and research. ISRO’s low-cost excellence in launch vehicles (PSLV, GSLV, LVM3) and satellite manufacturing has positioned India as a major space-tech player. Upcoming missions—Gaganyaan (human space flight mission targeted for 2027), Venus (2028), Mars (2030), a domestic space station (2035), and a manned lunar mission (2040)—along with the development of reusable NGLV (partially reusable medium to super heavy Next Generation Launch Vehicle) launchers reflect a long-term vision unmatched in the developing world. These advances spill into adjacent sectors such as communications, materials, manufacturing, and advanced engineering, fueling India’s broader technology ecosystem.

Simultaneously, India is investing aggressively in physical and digital infrastructure at a scale few countries can match. High-speed rail corridors, including the 1,08,000 crore INR ($13B) Mumbai–Ahmedabad line, massive airport projects like the 19,650 crore INR ($2.3 - 2.4B) Navi Mumbai Airport, and a national buildout of world-class highways under Bharatmala (44 economic corridors; 37 km added daily) and the $120B Sagarmala port modernization program are reshaping mobility and logistics. Industrial corridors such as the $90B Delhi–Mumbai Industrial Corridor—featuring 24 new smart cities—are designed to accelerate manufacturing, supply chains, and export capacity. India’s dependence on imported oil has also structurally declined, dropping 60% relative to GDP since 2008 as per analyst estimates, making the country more resilient to external shocks.

On the innovation front, India is backing deep-tech, semiconductor manufacturing, and research with unprecedented capital. The $10B Semiconductor Mission has kickstarted three major fabs, while thriving GCCs (Global Capability Centers) provide world-class design and engineering talent. The India Deep Tech Investment Alliance (IDTA) launched with $1B from U.S. and Indian investors, aims to work alongside the government’s RDI programme, further signaling deep-tech momentum. National research funding is evolving too—ANRF, modeled on the U.S. NSF will deploy $5.88B over five years, complemented by the upcoming 1,00,000 crore INR ($11.76B) RDI fund dedicated to AI, quantum, semiconductors, health tech, and advanced materials. anchored by policy hubs like GIFT City SEZ—India’s global fintech and capital-market zone with tax incentives and international currency access—India’s next decade is setting up to be one defined by scale, science, and sovereign capability.

Digitization Success leads to ease of doing business

Over the past decade, India has quietly built one of the most advanced public digital infrastructure stacks in the world. Three foundational layers - Aadhaar, DigiLocker, and UPI - have reshaped how citizens interact with businesses and how businesses operate at scale.

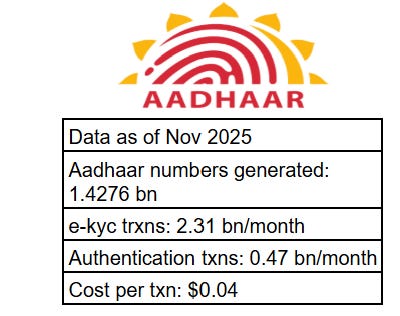

1. Aadhaar: Frictionless Identity at Population Scale

Aadhaar provides a universal, biometric identity system for over a billion people.

For businesses, this means:

1-minute KYC instead of weeks-long verification

Seamless onboarding for banks, telcos, fintechs, and gig platforms

Reliable authentication for subsidies, benefits, and credit scoring

Reduced fraud and duplicate identities

Aadhaar dramatically lowered the cost of verifying a customer—from dollars to cents.

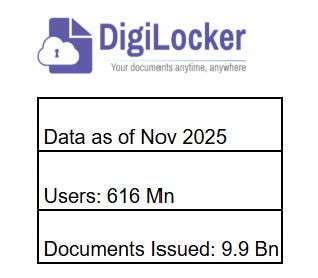

2. DigiLocker: Paperless, Instant Documentation

DigiLocker acts as a secure cloud vault for official documents issued by government bodies (licenses, IDs, school certificates, vehicle registrations, etc.)

Businesses gain:

Instant retrieval of verified documents

Zero physical paperwork or notarization

Secure APIs to integrate document fetch into onboarding

Faster compliance processing in sectors like BFSI, mobility, and education

For consumers, proving identity or sharing documents is now as simple as sharing a link.

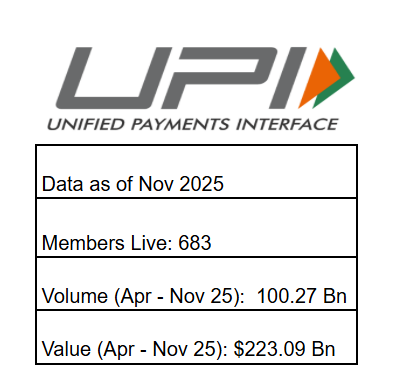

3. UPI: The World’s Most Scalable Real-Time Payment Rail

UPI has become the default digital payment method in India, with billions of transactions every month across QR codes, apps, and merchant platforms.

For businesses, UPI delivers:

Zero MDR (Merchant Discount Rates) for many transactions, lowering payment costs

Instant settlement and cash-flow visibility

Democratized acceptance—anyone with a smartphone or feature phone can pay

A unified ecosystem enabling lending, subscriptions, commerce, and micro-payments

UPI dramatically expanded the addressable market for digital commerce.

The Combined Impact: A New Operating System for Indian Business

Together, Aadhaar, DigiLocker, and UPI form a powerful digital backbone:

Lower customer acquisition costs

Faster onboarding & compliance

Reduced fraud / improved trust

Seamless payments and documentation

Inclusion of millions previously outside the formal system

This triad enables everything from fintech and ride-hailing to healthcare, edtech, quick commerce and logistics. It has turned India into one of the easiest large markets to launch and scale digital businesses, with infrastructure that rivals—and often surpasses—Western systems.

Challenges do exist

Challenges persist—income disparities, low productivity, limited formalization (with estimates such as only ~15–20% of the workforce being engaged in the formal sector), and a sizable shadow economy estimated at around 26.9% of GDP (estimates from World Economics). Market-access bottlenecks and corruption still create friction. Yet none of these materially slow India’s ascent. Productivity is rising, formalization is accelerating through GST/UPI/Aadhaar-linked systems, tax compliance has doubled over the past decade, and capital formation is at multi-year highs. The macro data is unequivocal: these headwinds remain manageable relative to the scale of structural reform and long-cycle growth already in motion.

In Conclusion

Despite global headwinds—ranging from trade tensions and protectionist tariffs to a rising interest-rate environment—India has maintained strong momentum, posting 7.8% and 8.2% GDP growth in Q1 and Q2 of FY2026. This resilience stems from the country’s services-heavy export mix and its reduced dependence on any single market, including the US. Coupled with a rapidly expanding domestic economy that adds roughly $1 trillion in GDP every decade, India is poised to be one of the most important growth engines in the global markets in the coming years. It is an opportunity that investors overlook at their own risk.

~ Deepak

Learn more about: Cornerstone Ventures | CGES Index

Disclaimer:

The data provided on this website (www.csvpfund.com) is for informational purpose only.

Any information provided on this website or any of the other digital assets owned & maintained by Cornerstone Venture Partners Fund, Mumbai, India (“CSVP”)and managed by the Investment Manager, Cornerstone Ventures Investment Advisers LLP, Mumbai India, does not constitute investment advice or investment recommendation nor does it constitute an offer to buy or sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell shares or units in any of the investment funds or other financial instruments.

The Cornerstone Global Enterprise SaaS Index (“CGES Index”) ™ is a trademark of CSVP. The CGES Index is created & maintained using a proprietary algorithm and is to be used for informational purpose only. It is not to be construed as an investment advice or investment recommendation in any of the constituent companies / stocks that are directly or indirectly part of the Index. The Index is created using publicly available data published on the websites of the respective companies. All data presented is as per our internal research and analysis leveraging publicly available data and is being presented only for academic deliberation and discussion purposes and is not to be viewed as any specific commentary / recommendation / evaluation / conclusion on any of the companies / stocks that are directly or indirectly part of the CGES Index.

CSVP also analyses, maintains, and publishes certain financial and non-financial metrics (“SaaS Metrics”) on the Index at an aggregate level, and not at a specific company / stock level that constitute the CGES Index. These SaaS Metrics are provided purely for informational purpose and CSVP assumes no liability for accuracy, suitability, or completeness of the SaaS Metrics. The SaaS Metrics are created using publicly available third-party information and CSVP does not claim any ownership of the sourced data. CSVP is not responsible for the accuracy, suitability or completeness of the information originally disclosed by the owner of the information and any information provided herein. CSVP accepts no liability and offer no guarantee as to whether the information is up to date, correct or complete.

CSVP may have used third-party data, information, and content (including all text, data, graphics, and logos) on the website. CSVP assumes no ownership and intends no infringement of rights, titles, and claims (including copyright, brands, patents and other intellectual property or other rights) of the respective owners or authorized users of the respective content. Use of such content is from publicly available sources and for indicative and informational purpose only in good faith. All trademarks and registered trademarks are the properties of their respective owners. This website may contain references or links to other websites. References and links to third-party websites do not mean that CSVP adopts the content behind the reference or link as its own. When first setting up the link, CSVP will have checked the linked site for illicit content and found none at that time. However, CSVP have no influence over the current and future design or content of such linked sites and will accept no liability for such content or design. Any use of these websites is at your own risk. The obligation of CSVP to remove or block the use of information according to the general laws from the time of knowledge of a concrete violation of the law remains unaffected.

.svg)

.svg)